Excavations in the Governor's Palace Cellar

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1721

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

2010

Excavations in the Governor's Palace Cellar

Principal Investigator

Marley R. Brown III

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Department of Archaeological Research

December 29, 1993

Re-issued

November 2002

The archaeological work in the Palace cellar grew out of the need to recover resources that were to be disturbed by the NEH utilities project. The NEH project necessitated construction of a large utilities trench below the western portion of the Palace cellar. Colonial Williamsburg's Department of Archaeological Research was asked to document and recover archaeological resources in the path of this trench. The project area was later expanded slightly to include analysis of the structural and historical development of the Palace. The information obtained from this project is particularly useful to those interested in issues relating to architectural changes in the Palace and how these changes might reflect changing preoccupations and attitudes during the eighteenth century.

The Palace cellar was first uncovered in the 1930s. The original excavators removed seven feet of fill to expose the remains of the foundations and the cellar floor. Documentary and photographic sources from the 1930s excavations indicate that the stone floor and brick paving had not been moved; therefore, the layers below the floor would have been undisturbed.

On September 22, 1993, archaeologists began work in the cellar of the western portion of the Governor's Palace. The archaeological assessment team addressed an initial question related to the laying of the paving stones were the stones laid in the first phase of the Palace construction, during the Lieutenant Governor Nicholson and Lieutenant Governor Spotswood periods, or were these stones a later addition, possibly laid during the reign of Lieutenant Governor Dinwiddie when many renovations to the Palace were undertaken? If the stones were a later addition, the underlying material should show evidence of a pre-existing living floor. The team also wanted to understand the relationship between the cellar floor and other features on the site.

Historical Overview of the Palace

Plans to build a home for colonial governors in Williamsburg, Virginia's colonial capital, began in the late seventeenth century. Initially colonial officials had no permanent residence in Virginia and lived in rented homes of Virginia gentry. Plans for a governor's residence were authorized by the colonial governments in Williamsburg and London in 1706, to be paid for by taxes levied on American colonists. Early in the eighteenth century the residence housed lieutenant governors while full colonial governors lived in and ruled from England. Late in the eighteenth century, Virginia's economic power and political resistance necessitated the presence of the full governor in the Virginia capital.

The design and placement of the governor's residence were developed by Williamsburg builder Henry Cary and Lieutenant Governor Francis Nicholson. Their plans were also influenced by Virginia gentry of the period. It was important that the Palace represent current architectural style, sufficiently grand for a person of undeniable status.

The Governor's Palace was comparable to the great manor houses in both England and colonial Virginia. The Palace represented civility and permanence in a colonial Virginia still considered very much a frontier wilderness. During the seventeenth century, cavaliers came to the Virginia colony to make their fortunes and quickly return to England. According to Graham Hood, an expert on issues relating to the Governor's Palace, and historian for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Lieutenant Governor Nicholson considered these facts when designing the residence. The elegant Georgian style of the Governor's Palace represented stability and spurred "cultural growth" (Hood 1991: 54).

In 1716, Lieutenant Governor Alexander Spotswood became the first colonial official to live in the Palace, although the residence was not completed until 1720. Spotswood did have some influence on the construction, however, making some changes in the original design. Lieutenant Governor Hugh Drysdale succeeded Spotswood in 1722. His rule was short-lived as he died soon after his arrival. He was the first official to die at the Palace. Drysdale was succeeded by Lieutenant Governor William Gooch, who lived at the Palace from 1727 to 1749. Apparently he did not maintain the Palace during his tenure because in 1749 the Council noted that the Palace was "in ruinous condition" (Hood 1991: 63) . Lieutenant Governor Robert Dinwiddie reigned from 1751 to 1758. During this period, significant changes to the Palace were made, some of which reflected general Palace refurbishment. Other changes, however, reflected changing attitudes in the colonial society of Virginia during the period. The addition of a ballroom and supper room extending from the north face of the Palace is evidence of a new preoccupation with entertaining. Barbara Carson describes this structural change in the Palace as part of a general trend beginning in the mid-eighteenth century (Carson 1987).

Lieutenant Governor Francis Fauquier followed Dinwiddie and was the last lieutenant governor to live in the Palace. During this period Virginia's wealth continued to make it England's prized colony, but political tension in the colony was also present. Unrest was motivated by governmental actions such as the Twopenny Act and the Stamp Act. At Fauquier's death in 1768, England believed that Virginia's wealth and power necessitated the presence of a full governor in the colony.

3Norborne Berkeley, Baron de Botetourt, was the first full governor to establish residence in Williamsburg and to live in the Palace. During his short reign he gained great respect in both Virginia and England and was known as a fair mediator between England and Virginia. Baron de Botetourt died in 1770 and was followed by John Murray, Earl of Dunmore, in 1771, the last colonial ruler in Virginia. Failing to command the respect of the Virginia colonists, Dunmore fled the colony in 1775.

At the end of colonial rule, the Palace still served as home for political officials. The first two governors of the commonwealth of Virginia resided in the Palace. The first governor, Patrick Henry, occupied the Palace from 1776 to 1779. Thomas Jefferson followed Henry in 1779 and represented Virginia from the Palace until 1780, when the capital of Virginia moved to Richmond. The decor and elegance of the Palace were not equaled after colonial rule, and in fact, the Palace was used as a hospital for American soldiers wounded during the battle of Yorktown. On December 22, 1781, the Palace was destroyed by fire.

In the 1930s the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation began restoration of the colonial capital, of which the Governor's Palace was a major element. The Palace was recreated on the basis of documentary and archaeological evidence, and the recreation was built directly on the original Palace foundations. The Governor's Palace recreation overlies one of the most prominent structures in American history.

Methods

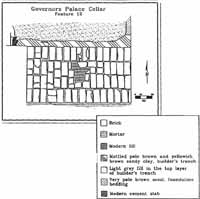

Colonial Williamsburg's stone masons had removed the paving stones within the immediate project area prior to the arrival of the archaeology team. The area was divided into five excavations units in order to maintain horizontal control of the area. The project area was later expanded to include two excavation units adjacent to the original project area (see plan map of project area).

Layers and features were excavated stratigraphically. Stratigraphy was determined by changes in soil color, texture, and cultural and natural inclusions. All soils were sifted through ¼-inch mesh. Chemical and flotation samples were also taken. Three pollen core samples were also extracted from (1) a general area within the project boundaries, (2) the original foundation builder's trench, and (3) the builder's trench associated with the chimney.

Artifacts were bagged, washed, recorded, and cataloged and date ranges were determined for diagnostic artifacts. A complete artifact inventory is found in the appendix of this report. These artifacts are stored at the Department of Archaeological Research.

Profile and plan drawings were made for each excavation unit and associated features. Detailed analysis of each feature and each separate context was also recorded during the excavation. These records are on file at the Department.

Results

The results of this project are informative of the historical and structural development of the Palace. During the excavation it was shown that some of the stone and brick paving laid in the eighteenth century had been disturbed in the 1930s recovery. The disturbed areas include portions below the doors in the cellar passageway, under at least one paving stone adjacent to the chimney, and below some of the brick floor paving in the vault rooms and in the service stair area. In these areas an organic, crushed marl fill was used to shore up and level disturbed and fallen paving. Early twentieth-century artifacts found in this fill suggest that the fill is associated with the 1930s reconstruction of the Palace.

Absence of an Occupation Layer

The paving stone and brick were laid on a 5 to 10 centimeter sand bedding layer. Few artifacts were recovered below the paving indicating that these were laid early in the construction sequence of the Palace. There is no occupation layer below the paving. Also, sand bedding found under the brick floor in vault room 1 suggests that the brick floor was laid at the same time as the paving stone.

The bedding sand seals subsoil. Some brick and mortar fragments ground into subsoil indicate a construction surface. This clay lens was very ephemeral and appears to be a working surface created during the time of the Palace construction. The lens varied in depth from 1 to 5 centimeters.

Foundations

The only features which cut into the subsoil base were builder's trenches and some twentieth-century disturbances around the service door and the mechanical room door. These disturbances are associated with the twentieth-century Palace reconstruction. The eighteenth-century builder's trenches are uniform in character. Foundation brick are two brick courses in depth below surface in all sample sections that were opened. The chimney builder's trench, which was determined to be a later addition to the Palace, is dissimilar in some respects to the overall foundation trenches. However, the chimney is still believed to be, and is so interpreted in this report, as an early addition pre-dating the placement of the paving stones. The specifics of this interpretation are detailed below.

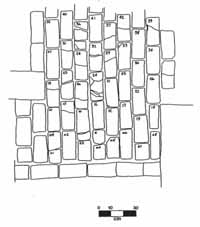

6 Figure 2. Plan of foundation wall uncovered during excavation.

Figure 2. Plan of foundation wall uncovered during excavation.

Interpretations

This section addresses three aspects of the Governor's Palace excavations that are considered to be most significant for understanding its structural development. These are (1) the foundation wall directly in the path of the utilities trench, (2) the chimney area, and (3) the brick paved floor area in vault room 1.

(1) The foundation wall, which lies in the direct path of the new utilities climate control system, suggests that a general plan and outline of the Palace was constructed using foundation brick regardless of whether walls were to be built over those foundations. Therefore, portions of the foundations do not have overlying walls. Evidence supporting this conclusion are the continuous builder's trench running along the north side of the cellar's main room and the interlocking of bricks underlying walls with the bricks that do not have overlying walls. Also, the brick foundation appears below each door area.

7(2) Excavations around the chimney in the main cellar room suggest that the chimney is a later addition, although how much later the chimney was constructed is not clear. Evidence suggests that it was probably added during the Nicholson and Spotswood period, which would be part of the first phase of Palace construction. That the chimney is a later addition is evidenced by the fact that the chimney builder's trench material is (1) darker and more organic, (2) contains less sand than the wall foundation builder's trench, (3) has a grayish sandy clay bedding as opposed to the sand bedding for the wall foundations, (4) contains much more brick rubble and nogging, (5) the brick at the bottom of the chimney builder's trench is 3 centimeters higher than the wall foundation brick found in that builder's trench, and (6) the angle of the cut for the chimney builder's trench is a 45 degree angle as opposed to the 90 degree angle cut of the foundation builder's trench. This evidence, as well as the fact that the chimney builder's trench cuts the original foundation trench, indicates the sequence of construction.

Although the chimney builder's trench is a later event, the chimney appears to be part of the early period of Palace construction. The chimney was constructed after the walls had been raised but before the paving stone had been placed. Evidence that supports this is that the chimney bricks do not tie into the above-ground cellar walls, nor do they tie into the below-ground foundation. Also, the chimney builder's trench cuts the foundation builder's trench. This indicates that the was had already been established when the chimney was constructed. However, the builder's trench for the chimney does not cut through the sand bedding for the paving stone and there is no evidence of intrusive bedding sand in the chimney builder's trench. This suggests that the paving stone had not been laid at the time the chimney was constructed. Since we interpret the paving stone as an early addition, suggested by the lack of evidence of a pre-existing living floor, the chimney must also be an early addition to the Palace.

It appears that the chimney pre-dates the paving but we cannot be certain how late it was added. Pollen core samples from each trench may be able to shed some light on the time differences in their construction. Diagnostic artifacts, which were not present in the chimney builder's trench, would have been useful.

(3) The brick floor area in the vault room 1 was analyzed to identify whether an organic layer seen in the doorway areas indicated a possible eighteenth-century living floor. After noting the ephemeral nature of this layer, architectural historian Mark R. Wenger suggested that the organic stain might represent the remains of the lower sill of a wooden door frame that had been removed. "The replacement of the wooden sill may be associated with the narrowing of the doors early in the Palace's development" (Mark R. Wenger, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation). The wooden sill would have been removed and overlaid with brick paving. Organic soils would have been used as fill to support the new brick replacement.

Archaeological evidence supports this hypothesis. Plan and profile drawings show the presence of the 15 cm × 15 cm × 180 cm organic layer that would have represented the original wooden door sill and, thus, the extent of the original doorway.

8

Figure 3. Plan of removed brick floor in Vault room.

This wooden sill was removed and filled with organic soils. All artifacts from these organic soils date to the eighteenth century. The organic soils stretched below several brick courses that wore laid when the doors were narrowed. Brick and mortar at both ends of the doorway indicate where the wooden door sill abutted the passageway walls.

Figure 3. Plan of removed brick floor in Vault room.

This wooden sill was removed and filled with organic soils. All artifacts from these organic soils date to the eighteenth century. The organic soils stretched below several brick courses that wore laid when the doors were narrowed. Brick and mortar at both ends of the doorway indicate where the wooden door sill abutted the passageway walls.

The wooden sill was replaced after the placement of the brick and stone paving. This is indicated by the removal of the paving sand bedding to replace the wooden sill. A small area of organic soils perpendicular to the removed sill fill is also believed to be another part of the replaced sill. This may be evidence of another portion of the wooden door frame. A clay pad layer overlying the foundation brick, similar to the construction layer overlying the foundation wall in the immediate project area, abuts both of the organic soil areas associated with the wooden sill. This clay pad outlines the east side of the wooden sill and the perpendicular organic portion that may have also been a part of the door fume.

Replacing of the sill and narrowing of the doorways does not coincide with the chimney construction. The paving bedding sand was cut underneath the brick floor for replacement of the sill. This sand bedding was not cut for construction of 9 the chimney. These facts suggest that the floor had been laid by the time the sill was replaced and the doorways narrowed, but had not been laid when the chimney was built.

10Conclusions

This archaeological assessment achieved two goals. First, the archaeological team was able to recover and document archaeological resources that were going to be disturbed by trenching for the utilities project. Second, archaeological methods were used to provide relevant information about the historical and structural development of the Governor's Palace. The most important information may be relatod to the chimney area.

Archaeology can be a powerful tool for understanding the historical development of structures. The archaeological evidence suggests that few changes occurred in the cellar areas of the Palace after its completion in 1720, during Lieutenant Governor Spotswood's reign. Cellar features, such as the chimney, reveal information about other areas of the Palace as well. For example, determining a period of the construction of the chimney in the cellar provides insights into heating the Palace hall, located directly above the cellar. James Deetz and Henry Glassie examined the issue of Georgian order and the Georgian mindset, noting that the presence of a chimney in the great hall is generally not considered a feature of Georgian architecture. "Glassie contrasts (early architectural styles) with the visitor's experience upon entering a Georgian house, where one was welcomed by an unheated central hall, showing only doors behind which the family carried out its daily functions" (Deetz 1977: 115) . According to the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's recreation of the Palace, a heated central hall does exist. Archaeological evidence suggests that the cellar 11 chimney was an early addition to the Palace, thus the Palace may be reflecting both Georgian and "Virginian" characteristics.

Historical records indicate that many changes were made to the Palace during the mid-eighteenth century. The addition of a ballroom and supper room on the north end of the Palace, during the reign of Lieutenant Governor Dinwiddie, is one example. These changes, in turn, reflect the changing preoccupations of eighteenth-century gentry with entertaining (Carson 1987: 7; Hood 1991).

Bibliography

- 1987

- The Governor's Palace: The Williamsburg Residence of Virginia's Royal Governor. Published by The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1977

- In Small Things Forgotten: The Archaeology of Early American Life. Doubleday Press.

- 1991

- The Governor's Palace in Williamsburg: A Cultural Study. Published by The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1993

- Personal correspondence.

Appendix 1.

Context Descriptions

Master context (1): Sand bedding for the brick and stone paving. Based on the fact that the same material is used for both stone and brick paving, it is believed that they were laid at the same time. This sand bedding was useful in determining an early date for the chimney and a post-paving date for replacement of the wooden sill in the doorways. Artifacts in this layer were scarce. This, plus no evidence for a pre-existing living floor in the cellar, indicates that the paving was laid early in the Palace construction (Munsell color of 10YR6/3).

Master context (2): Builder's trench-upper level clay layer. This layer was the top layer on all builder's trench sample areas except the chimney area. Sample areas were opened in each excavation unit to look for differences in trenches. This clay overlaid the foundation bedding sand (master context 7) in each sample area opened. The clay is redeposited subsoil (Munsell 2.5Y6/6 with mottling of 10YR5/6 and 10YR7/2).

Master context (3): Clay lens sealing subsoil and portions of original foundation. This is a thin clay lens 1-5 cm deep. The layer contains crushed brick and mortar fragments as if it were formed during construction of the Palace cellar. This layer is most prevalent in the passageway area and is stained red from the large amount of crushed brick. It is almost non-existent in the main room of the cellar, away from the walls. In these areas it is clearly a pure subsoil base (Munsell 10YR6/8 with mottling of 7.5YR6/6).

Master context (4): Twentieth-century organic fill containing crushed marl. This lens is found under door areas, at least one stone paving, the service stair bricks and small areas of brick paving in vault rooms. Artifacts including cigarette butts, wooden and paper matches, and metal pull tabs date this layer to the 1930s. This layer seems to have been laid to level off brick and stone paving that had either fallen or had been disturbed during the excavations (Munsell 10YR4/2).

Master context (5): Organic rich fill that is found only under doorways. This fill is believed to be the remains of the original wooden sill or the fill used to replace the sill. This layer takes the same form as the wooden sill. It extends 2-3 cm into the cellar passageway and 3-4 cm into the vault room. This layer contained only eighteenth-century artifacts. A clay pad, master context 3, abutted this soil suggesting that the clay was formed after the wood sill 14 was in place. The two were very distinct. This clay pad may have been used to steady the wood sill at the time of construction (Munsell 10YR3/3).

Master context (6): Brick course work in the foundation. The foundation extends two brick courses in depth below the subsoil surface. This is true in each sample area. Part of the foundation wall had to be removed for construction of the utilities trench. The foundation brick are set on sand bedding similar to the sand bedding used for the paving stone and brick. However, the sand bedding for the paving is given a separate context (master context 1) from the foundation bedding (master context 7) to distinguish the two. Brick and mortar samples were taken from the removed foundation. These are being conserved by the Department of Archaeological Research.

Master context (7): Bedding sand for foundation brick. It is similar, if not the same, as sand used for bedding for the stone and brick paving. Master context 7 is found at the bottom of each builder's trench sample area opened except the builder's trench associated with the chimney. Master context 7 is sealed by master context 2, the redeposited clay layer.

Master context (8): Mortar layer found below master context 4 and above master context 5. This mortar layer is very ephemeral and is believed to be associated with the replacement or decay of the wooden I sills. Master context 8 appears in all doorways. The mortar is a shell type.

Master context (9): Overlying clay layer in chimney builder's trench. Although it appears to be the same layer as master context 2 found in the foundation builder's trenches, there is no underlying sand bedding. This is redeposited subsoil. This layer contained much more brick and mortar than master context 2 and also contained nogging (Munsell 2.5Y6/6 with a mottling of 10YR7/2 and 10YR5/6).

Master context (10): Decaying organic matter. This material appears to be leaf matter at a late and preserved stage of decay. Master context 10 is found in a small section below the brick in vault room 1. It may be associated with twentieth-century disturbances (Munsell 10YR4/2 with a mottling of 10YR5/6).

Master context (11): Sandy clay (10YR4/6) bedding for chimney foundation. All other foundations have sand bedding (master context 7). This may help establish a later date for chimney construction (Munsell 10YR4/6).

15Master context (12): Fill and debris between bricks in vault room 1. Material which has filled in the gaps between brick flooring. This material does not seem to be associated with the eighteenth century (Munsell 10YR4/6).

Appendix 2.

Artifact Inventory

Note: Inventory is printed from the Re:discovery cataloguing program used by Colonial Williamsburg, manufactured and sold by Re:discovery Software, Charlottesville, Virginia.

Brief explanation of terms:

- Context No.

- Arbitrary designation for a particular deposit (layer or feature), consisting of a four-digit "site/area" designation and a five-digit context designation. The site/area for this project is "20AD."

- TPQ

- "Date after which" the layer or feature was deposited, based on the artifact with the latest initial manufacture date. Deposits without a diagnostic artifact have the designation "NDA," or no date available.

- Listing

- The individual artifact listing includes the catalog "line designation," followed by the number of fragments or pieces, followed by the description.

| 9 | Stone, unmodified |

| 1 | Coarse earthenware fragment, lead glaze |

| 21 | Brick bits |

| 2 | Shell |

| 7 | Shell mortar |

| 6 | Faunal bone |

| 1 | Glass fragment, wine bottle, highly degraded |

| 1 | Copper alloy fragment, unidentifiable |

| 1 | Iron nail, two to four inch, wrought |

| 6 | Iron nail, fragment |

| 2 | Iron fragment |

| 4 | Stone, unmodified |

| 5 | Shell fragment |

| 1 | Shell mortar |

| 8 | Brick bits |

| 2 | Iron, unidentified hardware |

| 2 | Iron nail fragment |

| 2 | Glass fragment, wine bottle, highly degraded |

| 1 | Stone, unmodified |

| 17 | Marl |

| 26 | Shell, twenty-four clam |

| 9 | Shell fragment, various |

| 1 | Stone, architect slate |

| 2 | Shell mortar |

| 8 | Brick bits |

| 1 | Copper alloy, wire |

| 9 | Iron nail fragment |

| 1 | Iron, unidentified hardware |

| 1 | Coarse earthenware fragment, unglazed |

| 2 | Ceramic tobacco pipe, imported, stem, 5/64 |

| 8 | Glass fragment, wine bottle, highly degraded |

| 2 | Stone, architect slate |

| 3 | Stone, unmodified |

| 13 | Shell, eight clam |

| 3 | Shell fragment, various |

| 8 | Marl |

| 11 | Brick bits |

| 1 | Other organic fragment, green, chewing gum |

| 8 | Iron nail fragment |

| 4 | Iron fragment |

| 4 | Glass fragment, table glass, colorless non-leaded |

| 10 | Glass fragment, wine bottle, highly degraded |

| 7 | Stone, unmodified |

| 18 | |

| 1 | Shell mortar |

| 11 | Brick bits |

| 1 | Iron nail, less than 2 inch, wire |

| 13 | Iron nail fragment |

| 1 | Glass fragment, table glass, colorless lead |

| 2 | Glass fragment, window glass, highly degraded |

| 1 | Iron nail, two to four inch, wire |

| 2 | Iron fragment |

| 29 | Shell, twenty six clam |

| 9 | Shell fragment, various |

| 1 | Marl |

| 2 | Stone, architect slate |

| 1 | Paper fragment, pink |

| 1 | Plastic fragment, brown |

| 1 | Aluminum closure, can, fragment, pop top |

| 1 | Ceramic tobacco pipe, imported, stem, 4/64 |

| 2 | Glass fragment, wine bottle |

| 1 | Glass bead, white, w/blue, Venetian trade bead, c. 18th C |

| 1 | Shell, tiny clam |

| 6 | Shell, one scallop, four clam |

| 1 | Shell fragment |

| 3 | Marl |

| 3 | Brick bits |

| 1 | Iron nail, triangular, wrought |

| 1 | Iron nail, two to four inch, wire |

| 3 | Iron nail, fragment |

| 1 | Iron fragment |

| 1 | Wood fragment, safety match |

| 1 | Paper fragment, book match* |

| 10 | Brick bits, four pieces burned |

| 1 | Iron, unidentified hardware |

| 1 | Iron nail fragment |

| 25 | Shell mortar |

| 4 | Brick |

| 2 | Glass fragment, wine bottle |

| 4 | Stone, unmodified |

| 7 | Shell mortar |

| 1 | Marl |

| 13 | Brick bits, one burned |

| 2 | Iron, unidentified hardware |

| 1 | Stone, unmodified |

| 2 | Brick bits |

| 1 | Glass fragment, wine bottle |

| 3 | Stone, fire-cracked rock |

| 15 | Brick bits |

| 31 | Shell mortar |

| 10 | Brick bits |

| 5 | Marl |

| 13 | Brick bits, three fragments badly burned |

| 13 | Marl |

| 1 | Ceramic tobacco pipe, imported, stem, 5/64 |

| 19 | Shell mortar |

| 1 | Faunal bone |

| 3 | Shell, small clam |

| 5 | Brick bits |

| 1 | Brickbat |

| 3 | Brick bits |

| 1 | Copper alloy, ring, copper wire |

| 1 | Iron nail, fragment |

| 1 | Glass fragment, wine bottle, highly degraded |

| 5 | Shell fragment |

| 45 | Brick bits |

| 1 | Paper fragment, polychrome, complete, paper patriotic sticker, c. 1900* |

| 1 | Quartz, unmodified |

| 7 | Paper fragment, book matches* |

| 4 | Wood fragment, safety matches |

| 10 | Wood fragment, bark fragments |

| 1 | Seed |

| 2 | Brick bits |

| 2 | Marl |

| 20 | |

| 1 | Shell, scallop |

| 1 | Iron nail, fragment |

| 1 | Glass fragment, table glass, colorless non-leaded |

| 1 | Glass fragment, wine bottle |

| 2 | Coal |

| 1 | Brick bits |

| 2 | Marl |

| 1 | Shell mortar |

| 1 | Stone, unmodified, with shell mortar |